What Is Behind Your Lath and Plaster Walls?

Knowing what's behind your plaster walls can make it easier to maintain them

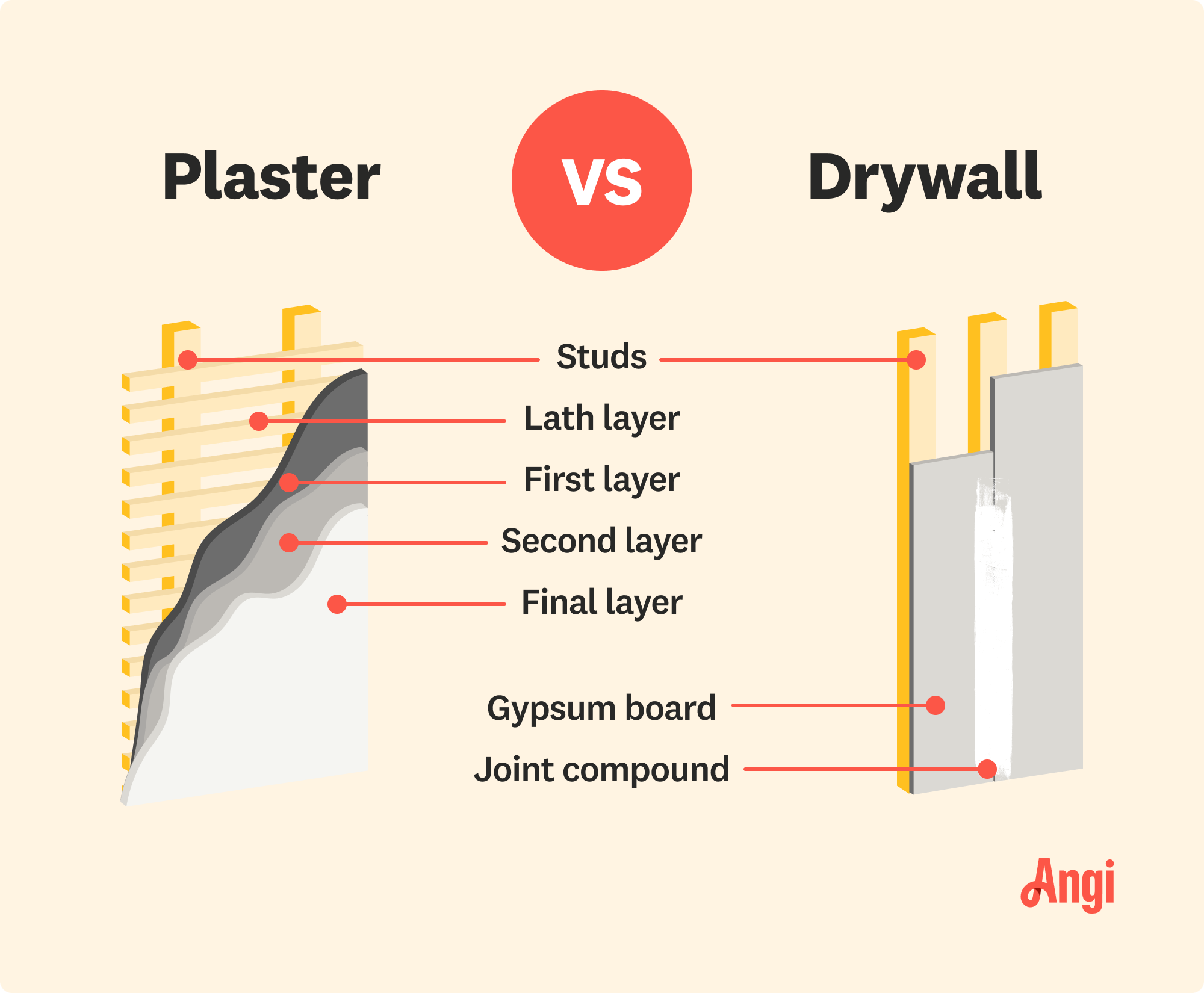

There are three different layers of plaster: the scratch coat, the brown coat, and the veneer coat.

Lath and plaster was a popular method of plastering homes between 1700 and 1940.

The process has largely been abandoned in favor of drywall.

Before drywall became the go-to for modern homes, plaster walls were everywhere. Many houses built before the 1940s relied on plastering because of its versatility, availability, and durability. But the method and materials used to apply plaster have changed in the intervening decades, which is why it’s not always clear what’s behind your walls.

Knowing when your house was built, as well as the signs and symptoms of damage to plaster walls can help you identify what type of lath and plaster you're working with. This helps you know how to keep your walls in good condition and know when it's time to call in a restoration pro.

What Is Lath and Plaster?

Lath and plaster was the go-to method of plastering homes between 1700 and 1940. Traditionally, plaster was a mixture of lime, aggregate, water, and animal hair. The hair was often horsehair. You might think the horsehair was an insulator, but it actually acted as a bridging agent. This means it held the plaster together and helped to prevent shrinkage

Modern plaster has a gypsum base, aggregate, water, and resin or acrylic components, rather than animal hair. It also sets and cures faster and is somewhat more resistant to moisture than traditional plaster.

The installation process for plaster consists of three different layers: the scratch coat, brown coat, and veneer coat.

Three layers are necessary with plaster to achieve a smooth, high-quality finish. The scratch coat is the first layer, applied on top of the lath strips. The second brown coat is another rough coat that adds volume and stability. The veneer coat is a thin, fine layer that adds a smooth, high-end finish.

Rock Lath and Plaster

Rock lath was a common base layer for plaster walls between 1900 and 1960. Unlike wood lath, which is applied in strips, rock lath is 4-foot long sheets of hole-filled, chemically treated rock that's designed for wet plaster application. The plaster flows through the holes in the same way it does with wood lath strips, forming a key that locks everything into place.

Calcimine

Calcimine wasn't an essential additive of lime-hair plaster, but it was a common finishing agent in pre-1940s properties. Calcimine is essentially a chalk powder mixed with water and glue. While it's more common as a finish for ceilings, it may also be the top coat on old plaster walls. This calcium carbonate paint softened the look of an otherwise stark plaster wall. Plus, it didn't react with the plaster and allowed contractors to paint over the surface with an oil-based paint right away. Without a calcimine coating, plaster walls needed around 60 days to cure enough to safely paint, or the oil in the paint would react with the plaster and result in a bad finish.

You’ll know your walls have calcimine in them if they’re prone to peeling or flaking. This material is also highly sensitive to water damage, and that might be the reason why your plaster walls are cracking or your wallpaper is bubbling.

Lath and Plaster vs. Drywall

With the widespread introduction of drywall in the 1950s, plaster quickly fell out of fashion. Drywall was cheaper and went up faster, so was quickly adopted by contractors and homeowners.

While they both serve the same purpose, there are a number of differences between plaster and drywall.

Drywall is easier to install since it comes in 4-by-8-foot sheets that connect directly to the wall. Plaster, on the other hand, is a multi-step process that takes days to complete, and requires 60 days of curing time.

Plaster is more labor-intensive and requires a higher degree of skill to install or repair, so it’s more expensive than drywall installation. Repairs are also more costly and usually more challenging when compared with the complexity and cost of repairing drywall.

Plaster has some insulating properties of its own, but still requires the use of modern insulation, like drywall does, to be a truly effective insulator.

If you're looking for noise reduction, then plaster is the better option—it's thicker and denser, so deadens sound between rooms more effectively than drywall. Additionally, plaster has a higher-end look than regular drywall, and walls can be textured like stucco, or have a glossy, soft finish.

How Is Lath and Plaster Done?

Lath and plaster is a simple but time-consuming process. The process begins with nailing wooden lath strips horizontally across the wall studs, spaced closely, but not flush, one above the other.

The lath boards are then coated with plaster. This is the scratch coat. During the coating process, some plaster oozes between the boards, not only filling the gap, but spreading a little above and below the gap, acting as a "key" and locking the plaster in place once it's dry.

Once the first coat is dry, the brown coat is added. The brown coat is a second coating of plaster used to thicken up and even out the first coat. And the veneer coat is a third layer of plaster, sometimes mixed with fine sand, to create a smooth finish.

How to Repair Lath and Plaster

Unlike drywall, fixing plaster is not a DIY job. It needs the careful attention of a skilled craftsperson, so you'll need to hire a local plasterer to complete any repairs. Painting over cracked plaster might appear to fix the problem, but it will make things worse in the long run. Even a simple touch-up to lightly damaged plaster needs a pro. Additionally, a pro can assess the state of the wall and the root cause of the damage, and can advise you on the extent of the repair. Remember, with plaster, what looks like some minor peeling can actually be significant historical water damage that requires completely rebuilding the wall surface.

Cracked Plaster

One of the most common issues with plaster is cracking. Hairline cracks are usually just a sign of the plaster aging, and are nothing to worry about. However, larger delaminating cracks that keep on growing can indicate that the plaster is pulling away from the lath. This requires immediate attention, particularly if it happens on the ceiling, as falling plaster chunks are heavy and dangerous.

Discoloring Plaster

If you notice your plaster becoming discolored and there's no obvious cause, the most likely culprit is water damage. It's often an early indicator that there is an active leak somewhere within your home. In this case, it's advisable to hire a nearby plumber to come and address the source of the leak. If the damage to your plaster is contained in a small area, you can potentially dry it out and apply a stain-blocking primer, then paint over the top. For extensive moisture damage, you'll need a plasterer to remove the affected plaster and rebuild it.

Bubbling Plaster

Bubbling plaster is a sign of a more significant leak. The plaster is essentially absorbing the water that's leaking out of your plumbing. The first thing to do, if you notice this happening, is to all a plumber to find and fix the leak. Then you need a plasterer to remove and rebuild the affected areas of plaster.

Should I Repair or Replace Plaster Walls?

Removing plaster and replacing it with drywall gets costly. In total, you're looking at $4.50 to $9 per square foot for replacing plaster with drywall. This breaks down as follows:

Cost of plaster removal: $1 per sq. ft.

Cost of drywall removal: $1.50–$3 per sq. ft.

Cost of painting interior walls: $2–$6 per sq. ft.

You'll also need to account for the cost to install molding, trim, and skirting, which can add another $5 to $20 per linear foot to your total. Depending on the condition of your walls, you may need to invest in other services, too, like the following:

Asbestos abatement or removal costs $11 to $13 per square foot.

Replacing or repairing ceilings costs between $45 and $90 per square foot.

Plaster repair costs $4 to $20 per square foot

Plaster can be expensive to repair. Since drywall is less costly, takes less time to dry, and looks exactly like plaster when repairs are done properly, companies often use drywall to repair plaster to help homeowners save money.

- Plaster vs. Drywall: Pros, Cons, and Costs

- How Long Does Plaster Take to Dry?

- Why Do Plaster Walls Crack?

- Can You Drywall Over Plaster? And Should You?

- Types of Plaster and Use Cases for Each

- Can You Paint Over Plaster Walls? Yes, But Take These Steps First

- Drywall vs. Plaster: How to Tell Which Walls Are in Your Home

- 7 Types of Plaster Finishes for Interior Walls

- Is Insulating Plaster Walls a Good Idea?

- Stucco vs. Plaster: Which Should You Pick For Your Home Exterior?